enteral feeding

- related: Medicine, ICU

- tags: #note

- source: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/enteral-feeding-gastric-versus-post-pyloric

Types

- nasogastric: most preferred

- nasoduodenal

- nasojejunal

- PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Consider if needed more than 4-5 weeks

- PEJ: jejunostomy

Types of feeding

- Bolus: patient in stable condition

- Continuous: less stable patient

Timing

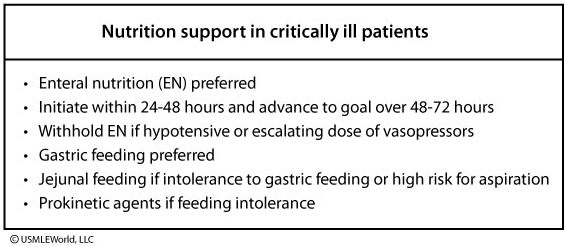

Nutrition is crucial to the care of a critically ill patient. Nutrition support is necessary to prevent cumulative caloric deficits and to aid recovery. Enteral nutrition (EN) is preferred as it is more physiologic and helps maintain intestinal structure and gut-barrier function. Early EN (within 24 to 48 hours) has been shown to decrease hospital length of stay and mortality.

EN is withheld if the patient is severely hemodynamically unstable with decreased intravascular volume due to the risk of bowel ischemia. Absence of bowel sounds or flatus is not a contraindication to early enteral feeding, even in patients who have undergone surgery for bowel perforation or colorectal disease. In this patient, the overall benefits outweigh the increased risk of vomiting.

Gastric feeding is preferred because of ease of tube placement and earlier feeding initiation. Prokinetic agents (metoclopramide or erythromycin) can be attempted if there is feeding intolerance. Post-pyloric tubes can be placed if there is feeding intolerance or the patient is at high risk for aspiration. Meta-analyses comparing gastric and small-bowel feeding show no differences in pneumonia, ICU length of stay, or mortality.

Assess feeding tolerance

- stool frequency

- diarrhea

- abd distension

- urinary output

- vomiting

- gastric residual volume

(See "Inpatient placement and management of nasogastric and nasoenteric tubes in adults"

Gastric vs Post-pyloric feeding

- Post-pyloric feeding has no benefit over gastric feeding

- Gastric feeding is preferred

- more physiological: buffer gastric acid, better pancreatic response, mimics physiological normality

- easier to begin: NG/OG easier to place

- more convenient: stomach can tolerate more load than small intestines and can act as reservoir. Also offers more flexibility in feeding regimen

- disadvantage of gastric feeding

- patients with delayed gastric emptying: use continuous feed

- risk for aspiration: use a smaller bore, elevate head of bed, reduce rate/volume of feeds, use lower osmolarity or more hydrolyzed formula, add prokinetic agent

POST-PYLORIC FEEDING

The most common indications for post-pyloric feedings include:

- Pulmonary aspiration.

- Severe gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and esophagitis.

- Recurrent emesis.

- Post surgery/multiple trauma.

- Abnormal gastric or antroduodenal dysmotility.

- Patients with decreased bowel sounds or those on paralytic agents. In both settings gastric motility may be impaired more than intestinal motility.

Passing a feeding tube beyond the pylorus is necessary in children and adults who are intolerant of intragastric feeds. This is most often due to a combination of GER, poor gastric motility and/or concerns about pulmonary aspiration. Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are also frequent candidates for post-pyloric feedings due to their underlying illness and frequent finding of gastric ileus. In trauma patients, early enteral nutrition is associated with fewer infectious complications than parenteral nutrition. A variety of in vitro and in vivo data also support the superiority of enteral over parenteral nutrition in a wide range of critical illnesses.

In children, jejunal feeds have traditionally been elemental or hydrolyzed and less viscous due to the narrow lumen of tubes needed to pass the pylorus, although polymeric feeds have also been tolerated. In adults, polymeric formulas are usually used except for those with malabsorptive disorders or pancreatitis. The sudden arrival of a hyperosmolar feed is likely to lead to abdominal cramping, hyperperistalsis, and diarrhea since the jejunum relies on a controlled delivery of isotonic substrate. In addition, the small bowel cannot expand its capacity as does the stomach, so jejunal feeds should be administered continuously by pump and never by bolus.

Advantages of post-pyloric feeding — Jejunal feeding has several advantages.

Minimize aspiration risk — The main advantage of post-pyloric feeding is that it may reduce the risk of GER and pneumonia.

Role in critically ill patients — Post-pyloric feeding has theoretical advantages in critically ill patients. Impaired gastric emptying is relatively common and thus feeding beyond the pylorus has the potential to deliver adequate nutrition without the need for parenteral nutrition. In addition, compared to gastric feeding, it may reduce the risks associated with high gastric residuals such as aspiration pneumonia. The delivery of a continuous feed to the jejunum also prevents gastric distension, thus potentially allowing for better respiratory function. The main disadvantages are the inconvenience, risks, and costs associated with placement of the tube beyond the pylorus. The rates of complications also depend on the severity of the underlying illness. As an example, prospective data show that critically ill children with shock had a higher incidence of gastrointestinal complications (eg, diarrhea, distension) with post-pyloric feeds than children without shock.

Several studies have examined these issues in critically-ill patients; not all of which reached the same conclusion. A 2015 meta-analysis included 14 randomized controlled studies that compared gastric versus post-pyloric feeding in 1109 critically ill patients. There were no significant differences in duration of mechanical ventilation or mortality but post-pyloric feeding was associated with a reduction in pneumonia as compared with gastric feeding (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.51-0.84).

Canadian clinical practice guidelines also noted that small bowel feedings were associated with a lower incidence of pneumonia in critically ill adults (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.60-1.0), and therefore recommend routine use of small bowel feedings in centers where this is feasible. Canadian ICUs using these guidelines reported higher rates of adequacy of enteral nutrition (percentage of prescribed energy needs actually received) compared with sites less compliant with these guidelines.

Benefits in acute pancreatitis — By bypassing the mouth, stomach and duodenum, jejunal feeds minimize the stimulation of pancreatic exocrine secretions. Accumulating evidence has suggested that post-pyloric feeding is safe and may also reduce complications. The hypothesis underlying this benefit is that enteral nutrients maintain the intestinal barrier. Bacterial translocation from the gut is probably a major cause of infection in the setting of acute pancreatitis. In addition, another major advantage of the intestinal route is the elimination of the complications of parenteral nutrition such as catheter sepsis (2 percent even if the catheter is managed appropriately) and less frequent complications such as arterial laceration, pneumothorax, vein thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, hyperglycemia, and catheter embolism. Although the results of large controlled trials are awaited, cautious use of post-pyloric feeds in acute pancreatitis should be strongly considered. A meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials confirmed that enteral nutrition in the setting of acute pancreatitis was associated with significant reductions in length of stay and infectious complications. Indeed, guidelines recommend enteral feeding rather than parenteral nutrition in patients with moderately severe and severe acute pancreatitis who cannot tolerate oral feeding.

Disadvantages of post-pyloric feeding — The main disadvantages of post-pyloric feeding are related to difficulty with the placement of the tubes, clogging, and maintenance of their proper positions. In practice, success rates at post-pyloric placement can exceed 90 percent, regardless of technique (air insufflation, or use of erythromycin as a prokinetic agent). Feeding intolerance may also be a problem. A systematic review of transpyloric feeding in preterm infants found no significant growth benefit, but noted an increased mortality rate and an increased rate of feeding cessation due to GI symptoms among those infants assigned to receive transpyloric feeding.

Difficulty with placement and ease of displacement — As with nasogastric tubes, nasojejunal tubes are very prone to accidental removal. Jejunal tubes are generally of finer bore than gastric tubes and thus frequently occlude, particularly if more viscous feeds and medications are given via this route.

Ideal positioning of post-pyloric feeding tubes is into the distal duodenum or jejunum (ie, beyond the ligament of Treitz). An adequately sited post-pyloric tube (verified radiographically) virtually eliminates tracheal aspiration and is less likely to become dislodged, even in patients with persistent cough or vomiting. Although feeds can be given through tubes located more proximally in the duodenum, this is not an ideal location: a precise location in the duodenum is difficult to maintain, allows duodenogastric reflux of feed, and hence can contribute to gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration. Tubes in the proximal duodenum may also recoil into the stomach.

Intestinal perforation occurs more often with jejunal tubes than with intragastric tubes, although the introduction of softer and more flexible materials reduced the incidence of this complication [46,47]. Formation of an enterocutaneous fistulae has also been described [48]. Most reports of this type of complication have been in premature infants [49,50].

There are several methods used for placing post-pyloric tubes. Endoscopic placement of a jejunal feeding tube is commonly carried out, and allows placement under direct vision. Fluoroscopy facilitates the placement of jejunal feeding tubes, particularly of gastro-jejunostomy tubes, but requires skilled radiologic support and exposure to radiation [51,52]. More recently, an electromagnetic-guidance technique proved faster (1.7 hours versus 21 hours) and more successful (82 versus 38 percent) than "blind" placement of a post-pyloric enteral feeding tube [53]. In general, small-bore tubes are more easily placed than larger tubes.

There are several less invasive techniques that have been described. Jejunal tubes with a pH sensitive tip have been successfully passed in children [54]. Weighted tubes have generally been no more successful than unweighted ones [55]. Gastric insufflation of 20 mL of air with an unweighted tube allowed 23 of 25 tubes to be advanced into the small bowel, compared to 11 of 25 in the control group in one study [56]. Other authors have used either erythromycin [57] or metoclopramide [58] to advance transpyloric tubes with some success. A meta-analysis of metoclopramide for this purpose noted that efficacy has not been demonstrated but that studies have been generally unpowered [59].

Feeding intolerance — A significant problem in some patients occurs with rapid entry of formula into the jejunum. This may follow the rapid infusion of feeds via jejunal tubes, or rapid gastric emptying of gastric bolus feeds. These patients develop a "dumping syndrome," with symptoms of faintness, palpitations, and sweating, often accompanied by pallor, tachycardia, rebound hypoglycemia, and diarrhea. It usually requires slowing of the rate of feeding or a change in formula. Although whole protein, complex carbohydrate feeds can be infused into the jejunum at low volumes, caloric requirements often require hydrolyzed protein formulas with medium-chain triglycerides and corn syrup/glucose polymer as sources of fat and carbohydrate, respectively. The addition of complex carbohydrates (eg, cornstarch) can reduce rapid glucose shifts and "dumping" symptoms that occur in patients given standard intragastric feeding regimens [60].

LONG-TERM PRE- AND POST-PYLORIC FEEDINGThe indications for pre- and post-pyloric feeding also apply to the more permanent enteral feeding tubes. The placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) has now become common practice in patients requiring enteral feeding for more than four to five weeks. A feeding jejunostomy tube generally requires surgical placement, although endoscopic placement of jejunostomy tubes has been described (PEJ) [61-64]. One series in children has found this technique to be feasible in children as young as four years [65]. In adults with a body mass index (BMI) >25, the success rates of direct endoscopic jejunostomy placement was lower (67 versus 87 percent) than in patients with a BMI <25, and four out of five serious adverse events occurred in those with a BMI >25 [66]. In the presence of any esophageal obstruction, radiological gastrostomy placement has been used with some success [67], although the choice over a surgical gastrostomy clearly depends upon availability of local expertise.

Both surgical gastrostomies and PEGs differ from the nasogastric feeding in that they tether the gastric wall to the anterior abdominal wall. This is a theoretical problem with patients who already have disordered upper gastrointestinal motility, since this tethering can potentially worsen gastroesophageal reflux. If a motility disorder is strongly suspected, formal motility assessment of the upper gastrointestinal tract may be carried out prior to the procedure. If there is significant delay in gastric emptying or disordered antroduodenal motility, placement of a PEJ or surgical jejunostomy may be indicated instead of PEG.

In settings where gastrostomy feeds are no longer tolerated, a trial of jejunal feeds can be performed by placing a jejunal tube alongside an existing PEG, or by placing a PEG tube with transgastric jejunostomy tube (PEG-J), through which where a jejunal extension tube allows transpyloric feeding. These techniques provide a short-term feeding solution and may predict the response to a surgical jejunostomy or PEJ. However, they are seldom a long-term solution since these tubes also tend to recoil into the stomach, become clogged, and may be of little value in preventing pre-existing oropharyngeal aspiration [6,68]. PEJ tubes have significantly better long-term patency and stability of feeding access compared with PEG-J tubes [63,69].

SOCIETY GUIDELINE LINKSLinks to society and government-sponsored guidelines from selected countries and regions around the world are provided separately. (See "Society guideline links: Nutrition support (parenteral and enteral nutrition) in adults".)

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

●The choice and route of enteral feeding is based upon the clinical setting, expected duration that support will be required, and assessment of the risk of complications. Enteral rather than parenteral nutrition is preferred in most patients (unless there are specific contraindications) since it is a safer and more physiological means of nutritional support. (See 'Issues for deciding upon the type of enteral nutrition' above.)

●Most patients can be started on low volume continuous intragastric feeds. However, we suggest beginning with jejunal feeding in patients with any of the following features: recurrent aspiration of gastric contents, esophageal dysmotility with a history of regurgitation, or delayed gastric emptying ([Grade 2C](https://www.uptodate.com/contents/grade/6?title=Grade 2C&topicKey=GAST/2583)). (See 'Gastric feeding' above.)

●Additional settings in which post-pyloric feeding can be considered include: severe gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and esophagitis, recurrent emesis, post-surgery/multiple trauma, gastric, antroduodenal dysmotility, patients with decreased bowel sounds and those on paralytic agents (where gastric motility may be impaired more than intestinal motility). The main disadvantages of post-pyloric feeding are related to difficulty with the placement of the tubes, clogging, and maintenance of their proper positions. (See 'Post-pyloric feeding' above.)

●There continues to be practice variation in use of post-pyloric versus gastric feedings in critically ill patients. In a pediatric intensive care unit (ICU), post-pyloric feeding is often used due to relative ease of placement, whereas in many adult ICUs, gastric feedings are often used initially because of the inconvenience of placing and maintaining post-pyloric feeding tubes in older patients.

●Enteral feeding can be associated with complications. The importance of assessing each individual's risk of GER and possible aspiration pneumonia cannot be overstated. (See 'Disadvantages of gastric feeds' above and 'Disadvantages of post-pyloric feeding' above.)